My Journey into Chinese Landscape Painting

In my childhood, serendipity strokes, I began learning traditional Chinese painting under the guidance of a seasoned teacher. As I dipped the brush into water, drained it, and touched it to the ink, delicate ink strokes on pristine rice paper effortlessly unfolded, ushering me into the enchanting world of landscape painting.

Following my teacher’s lead, I started with meticulous copying, beginning with a single stone or a solitary tree. My interest soared, and not only did I paint during classes, but I also embraced the art at home, diligently replicating every stroke from the instructional book. Gradually, these individual stones transformed into mountains, and singular trees evolved into dense forests. Given another instructional book by my teacher, I ventured into painting entire scenes. Using a small brush to outline the contours, I rubbed the paper to create the folds of the mountains. Witnessing the mountain range slowly emerge before my eyes, a profound sense of accomplishment enveloped me.

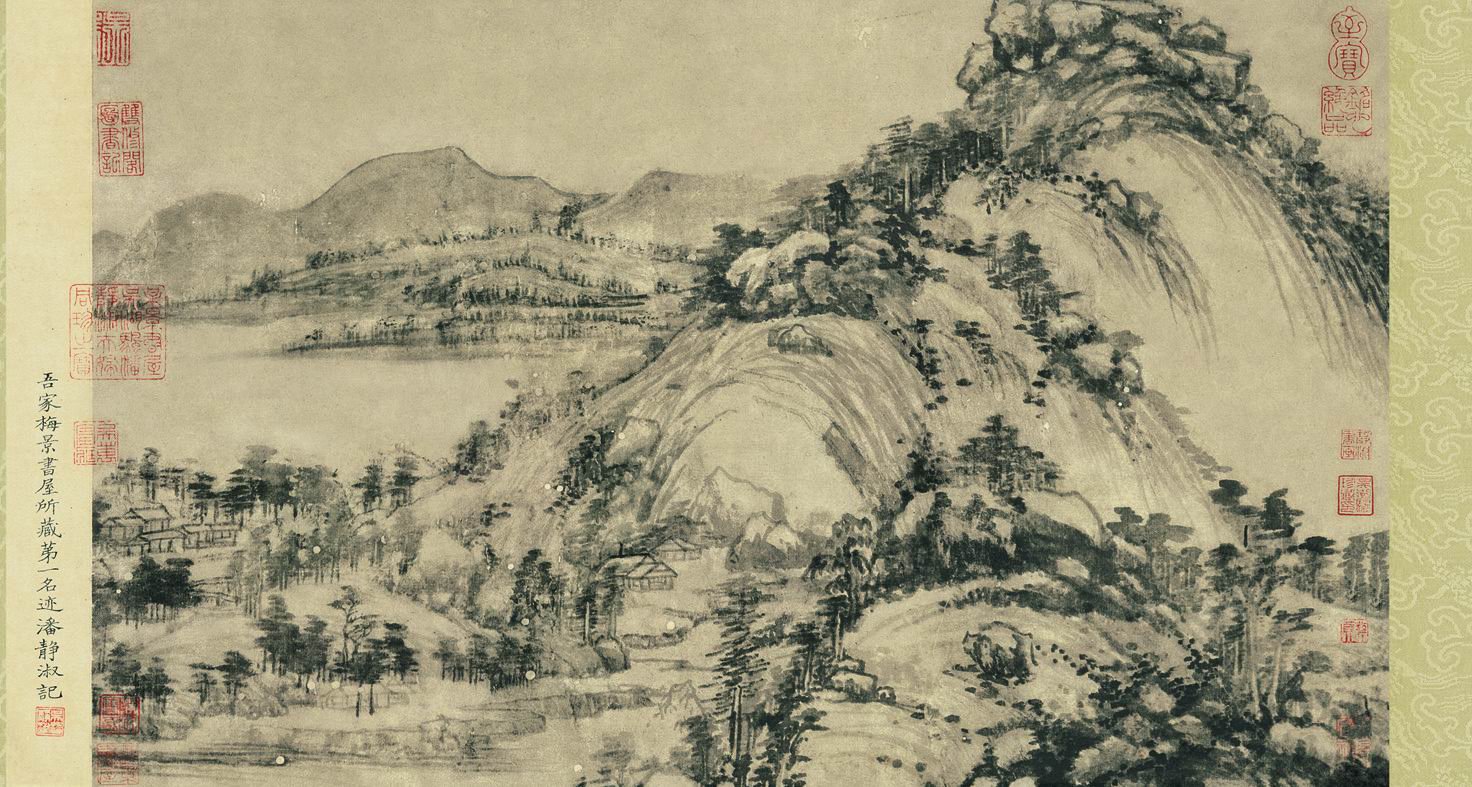

However, after months of replication, a sense of monotony began to overshadow my initial enthusiasm. The question arose: weren't these just mountains and water, and what was the significance of painting so many? Sensing my confusion, my teacher silently presented a different book, flipping through its pages and asking, "Do you see the differences in these stones?" I shook my head. He turned to a page displaying a part of the famous painting "The Dwelling in Fuchun Mountain" and narrated the artist's story. Huang Gongwang, wrongfully imprisoned during his official career, started learning painting at the age of 50 and spent the last seven years of his life secluded in the mountains, creating this masterpiece. "His technique for painting stones is called 'pi ma cun.' Given what I just told you, do you have any insights?" Studying the intricate details of the painting, I marveled at the uneven but orderly ink lines forming the mountains and rocks, the light ink portraying mist and simplicity. It truly reflected the undulating journey of life and steadfast, serene beliefs.

portion of Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, by the Yuan Dynasty painter Huang Guangwang (1269 - 1354)., Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), ink on paper hand scroll, The work is currently kept in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou.

From that moment on, I couldn't help but delve into the background stories of the paintings before attempting to replicate them, imagining and understanding the emotional states of the original artists. Gradually, stroke by stroke, I began to appreciate the art form. I particularly enjoyed observing the rocks; different stones required distinct techniques. When the mountain terrain was steep, the artist used 'axe-chopping' strokes to depict the ruggedness and hardness of the rocks. In contrast, when the mountains had gentle slopes, 'pi ma cun' strokes conveyed the loose and elegant texture of the soil, revealing the artist's inner tranquility. Despite the timeless nature of mountains and waters, I could now discern the subtle differences.

After countless strokes, I came to realize that Chinese painting is not merely about representing the objective world; it is an exploration and expression of the artist's inner world. Only through contemplation and reflection can one grasp its soul and infuse spirit into each brushstroke.

In today's era of information overload, traditional Chinese painting has lost some of its allure. Perhaps the reluctance to slow down, engage with artworks, and attempt to comprehend the artist's emotions through brushwork has led many to lose patience with this process. Yet, this is precisely the charm of traditional art. Armed with patience and introspection, I am committed not only to preserving the tradition of Chinese painting but also to slowing down my own life, discovering more of its wonders.